Most important lesson I learned out of school

A long time ago, a time so long ago that it’s no longer included in my resume, I was an intern at one of the pharmaceutical manufacturing companies in Singapore. It was here that I learned the most important lesson outside of formal education setting: Root Cause Analysis (RCA).

I have found RCA to be quite a universally applicable troubleshooting process to various problems that I have encountered while working as a process engineer and as a software engineer.

Each organization might have a slightly different implementation of RCA. The 5-step RCA process I am describing below is from my very fallible memory, distilled through the many times I have used it in different scenarios. It was not intended to be an exact replica of the RCA process applied at my previous internship.

Step 1: Problem Description

The purpose of this step is to immediately record all the relevant details regarding 1. the scope of the problem, and 2. any action taken to contain the problem.

It is important to conduct this brief step as soon as the problem is first noticed, so that valuable information is collected for subsequent investigation into the root cause.

Step 2: 5W1H

This step is where all the information recorded in step 1 above is organized into answers for the questions of who, what, when, where, why, how surrounding the problem.

It is especially critical to fully describe the problem, especially in dealing with software bugs. The goal of this step is simple: to provide enough information so that the problem can be reproduced. I have found that this is the fundamental difference between a good bug report and a bad one.

As to what information is usually sufficient for reproducing a bug, it depends on the software. For example, reproducing a web app bug would require the client’s user ID, their browser details, specific sequence of actions leading up to the unintended outcome, what the intended outcome should be, etc. I have found screenshare/videos/gifs to be helful tools in communicating the problem.

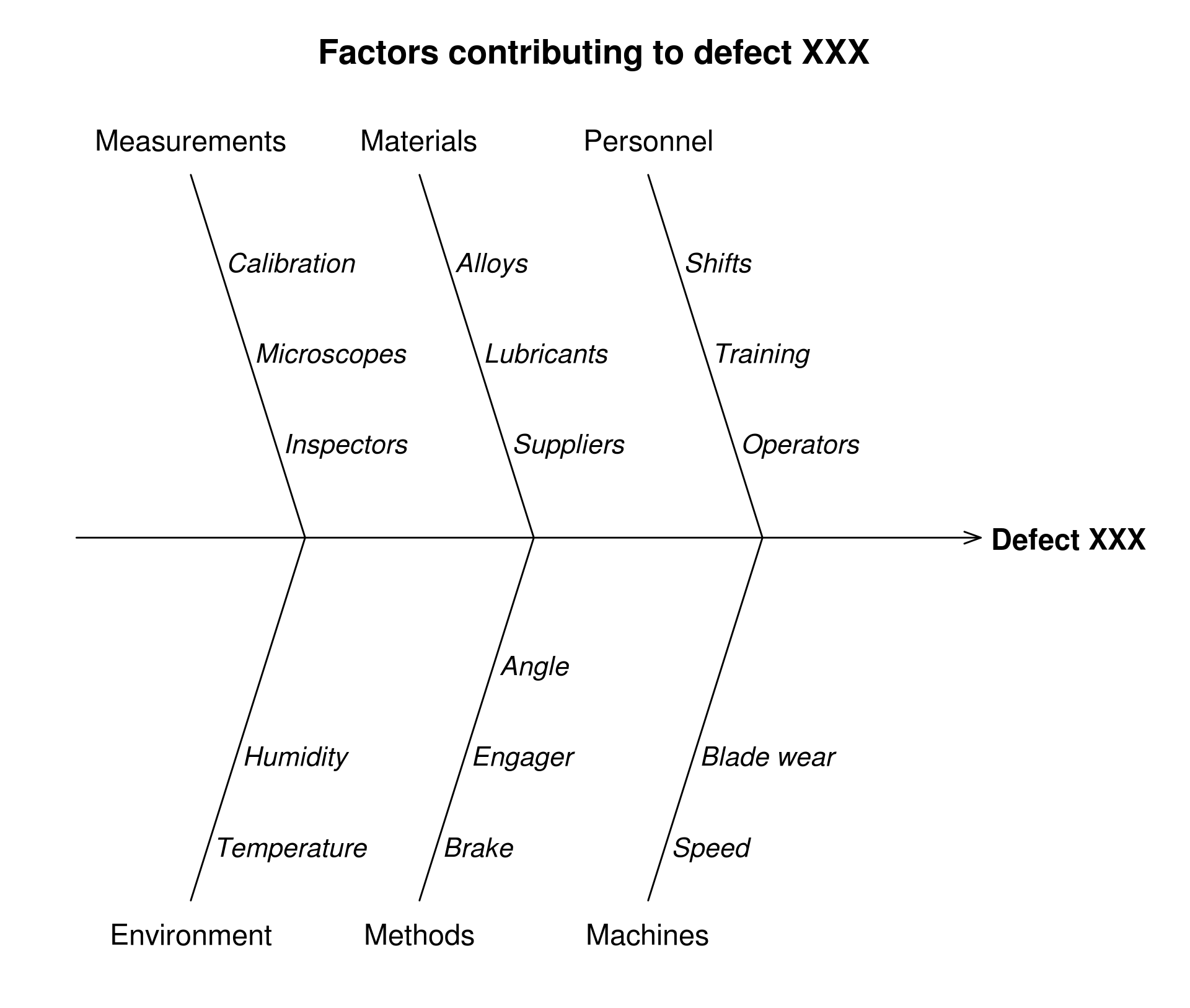

Step 3: Fishbone Diagram

This step of the problem lists down all potential causes for the problem, classified into 6 categories: Man, Material, Measurement, Machine, Method, Mother nature (Environment). It is helpful to have these categories in a template because some of them, such as Measurement, are easily overlooked, even though they are as often the root cause as others.

The categories listed above are what I learned in pharmaceutical manufacturing. The ones to apply to software engineering might be slightly different.

This is the only step in RCA that I find to be of a lower importance in software engineering. Fishbone diagram should only serve as a quick brainstorm to roughly scope the parts of the system where the root cause of the problem could reside.

Step 4: 5 Whys

5 whys is a common troubleshooting technique because it is simple yet incredibly powerful. Using 5 whys, we can arrive at the root cause of the problem by successively asking why, until we can identify the process that causes the failure.

If you fixed a bug in your product, and somehow keep seeing similar bugs popping up time and again, it is because you did not identify and fix the root cause of the problem. Identifying the line of code that causes a bug does not mean that you have arrived at the root cause. You need to keep questioning the process that allowed that buggy line of code to be merged into your code base.

Step 5: Corrective Action & Preventive Action

Knowing the root cause of the problem, we can implement actions to correct the problem and rectify any impacted data, allowing the system to resume normal operation.

Preventive actions can then be implemented to eliminate the root cause, improve the process, and preventing the problem from ever occuring again.

Despite my firm belief in the power of RCA, I don’t think it can be strictly applied in software engineering.

I learned about RCA in pharmaceutical manufacturing, an industry that is fundamentally different from software engineering, especially in terms of speed. A manufacturing plant might produce the same product with the same specs for 100 years. The average time from FDA application to approval of drugs is 12 years. Consistency in quality is absolutely critical for a pharmaceutical product.

On the other hand, the survival of a software depends heavily on its ability to continuously integrate and deploy new features. If this RCA process were to be perfectly applied in software engineering, all software would have 100% test coverage, and new features would take forever to be deployed.